The Separate Baptist Revivals in the South,

1750-1790

Garry D. Nation

The Separate Baptists during the decade leading up to and including the Revolutionary War pursued three tasks, not necessarily by design: keeping strains of revival going in a time of national spiritual decline, finding a role for themselves in American life, and find a unity with other Baptists. As a whole they succeeded in all three.

Keeping Revival Fires Burning

Wartimes are almost invariably times of spiritual slackness and decline in a nation. Praying people's prayers are turned toward the defeat of enemies rather than the salvation of their neighbors or even of their own souls. During the Revolutionary War there was a slowing of Baptist growth, which was perhaps more marked because of the Methodist revivals which had rapid growth through the war years, especially in Virginia. But a slowing in the growth rate is not a decline, and Baptists were not idle, nor were they becoming stagnant.

It is true that from 1775 and for the next 10 years there were complaints of “coldness and dissension: in the churches and that many felt the revival days were in the past. However, one contemporary witness “records that thirty-seven new churches were organized during the Revolution in twenty-eight different Virginia counties. In thirteen of these counties there had been no Baptist church before.”1

Also, there was growth in parts of North Carolina where the war had not come. Elijah Baker was busy planting churches on the eastern coast of Virginia. Silas Mercer was continuously preaching throughout North Carolina during the war, at least once a day for six years. In 1775 the Grassy Creek community felt a notable revival. In South Carolina, Elhanan Winchester led a revival in which 240 members were added to Welsh Neck Church in 1779. 2

Samuel Harris continued to be active as well. The General Association of Separate Baptists, established in Virginia 1771 after the dissolution of the old Sandy Creek Association, elected and ordained Harris as “apostle” in 1774 and commissioned him to “pervade” the churches, attend to ordination, set things in order in the churches, and be accountable to the Association and to the churches he served. 3

Daniel Marshall went to Georgia in January 1771 and founded the first Separate Baptist church there at Appling in 1772. Lumpkin says he was the only pastor in any denomination who remained in his pastorate throughout the Revolutionary War. Ibid., 135. He continued ministering there until his death at age 78. Witnesses recorded his last words. He said that God had shown him “that He is my God; that I am His son; and that an eternal weight of glory is mine!” Turning to his tearful wife he urged, “Go on my dear wife to serve the Lord. Hold out to the end. Eternal glory is before us.” After several minutes he called his son and told him, “I have been praying that I may go home tonight. I had great happiness in our worship this morning, particularly in singing, which will make a part of my exercises in a blessed eternity.” He then closed his eyes and “fell asleep in Jesus” at dawn, November 2, 1784.4

Two other figures from the second generation of the Separates rose to prominence during this time, John Leland and Richard Furman.

John Leland came to Virginia from Massachusetts in 1777. A vigorous itinerant preacher, he ranged as far south as the Pee Dee region in South Carolina. In 1779 he concentrated his efforts on the eastern half of Virginia. Between November 1779 to July 1780, he baptized 130 persons in York County.

Richard Furman began preaching almost as soon as he was converted, persevering despite intense mockery from his peers. In 1774 at age nineteen he was ordained and began serving as pastor of the High Hills of Santee Church, and also made preaching tours throughout South Carolina. On one occasion he baptized enough people to start a new church. He was a strong and vocal patriot during the Revolution, and the British occupation in 1780 forced him to interrupt his ministry until after the war.

Finding a Role in America

As a rule, Baptists like Furman were active patriots in the Revolutionary Cause. Purefoy says Marshall also was “a strong friend of the American cause, and was once made a prisoner, and put under a strong guard, but obtaining leave of the officers, he commenced and supported so heavy a charge of exhortation and prayer, that, like Daniel of old, while his enemies stood amazed and confounded, he was safely and honorably delivered from this den of lions.” 5 (I am not sure exactly what this means, but apparently his fearless preaching somehow led to his release.)

In Virginia, “Baptists formed a whole company to fight for the Revolutionary cause, which they considered their own. They also asked and received permission to furnish chaplains for their troops who served in the army.” 6 One result of this active participation in the American cause was to help eliminate the lingering prejudices that remained against the Separates. Among other things, they proved that they too were Americans.

There were exceptions, like Philip Mulkey who apparently harbored Tory sentiments, or at least was a non-resister. Besides this, nothing is known of his activity during the war. The last ministerial service he is known to have performed was in the presbytery that constituted Cheraw Hill Church in 1782, just after the war's end. But in 1790 he was excommunicated, and the churches were warned against him for “adultery, perfidy and falsehood long continued in.” Again in 1795 another warning against him was published claiming that he was still practicing “Crimes and Enormities at which humanity Shudders.” That is all that is known of his later history, and perhaps is the reason why so little memory of him is preserved save for his missionary work early in the movement. His son Jonathan became the pastor of a church in Tennessee in 1809, and it is possible that the family relocated there. 7

Finding a Unity

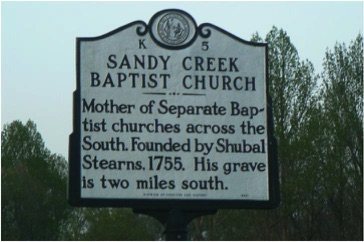

From the time that John Gano first visited the Sandy Creek Baptist Church there were stirrings of a desire for unity between groups that held Baptist principles in common. Interestingly, it was the established Regular Baptists who sought it first. In 1772, the Kehukee Association of Regular Baptists, made overtures to unite with the North Carolina Separates but were rebuffed. The Separates had their reasons for declining the invitation, some of them social, such as differences in manner of dress. But the real issue was one of discipline and polity: the Separates felt that the Regulars were not strict enough in requiring conversion before baptism. 8

Over the next decade, however, negotiations continued back and forth. The Separates may object to the “creedalism” of the Regulars, while the Regulars would express suspicion of Arminianism in the Separates. Over time, however, each group was getting more used to the other and more accepting of the other's ways. It would not be until after the Revolutionary War, though, that unification would take place, and it would not be until the revivals of the new century that it would be a complete melding.

Previous: Division and Decline

NOTES

1 Attributed to Ryland in Lumpkin, 134.

2 Townsend, 296.

3 Lumpkin, 102.

4 Purefoy, 296.

5 Ibid., 295f.

6 William R. Estep, “Southern Baptists in Search of an Identity,” in Estep, 149.

7 Townsend, 125n.

8 Source 21 (2).

- VI-

"Greater Love Hath No Man Than This"

The Revolutionary Period, 1771-1781